Article: The Magical Forest of Reading and Writing: Redefining Bilingual Literacy through Hybrid Learning

Abstract

Bilingual literacy in elementary education continues to face challenges related to motivation and performance. The Explorers of the Forest of Reading and Writing project proposes a hybrid model that combines station rotation, adaptive platforms, and playful learning experiences to transform reading and writing instruction in bilingual settings. Grounded in frameworks such as COVA, Universal Design for Learning (UDL), and constructionism, the model integrates digital tools and face-to-face interaction to enhance motivation, strengthen reading comprehension, and improve Spanish writing while building strong foundations for English literacy. This article presents the theoretical foundations, pedagogical vision, classroom implementation, and lessons learned through a participatory action research process aimed at refining the model and demonstrating its viability and sustainability.

Keywords: bilingual literacy; hybrid learning; motivation; action research; Universal Design for Learning (UDL).

In bilingual elementary education, literacy gaps persist as a significant challenge. Although reading and writing are essential for lifelong learning, many students lose motivation when instruction depends on uniform or standardized methods. Research indicates that bilingual learners benefit from differentiated approaches that value both their first and second languages (August & Shanahan, 2006). Without a solid foundation in the first language, cross-linguistic transfer weakens, limiting comprehension and academic development (Cummins, 2000).

Planting the Seeds of Bilingual Literacy in the Magical Forest

Blended learning offers a promising solution. Beyond simply combining digital tools with face-to-face instruction, it positions students as active explorers of their own learning. Christensen, Horn, and Johnson (2017) describe this as disruptive innovation, in which technology is intentionally integrated to transform teaching practices. Hughes and Roblyer (2022) emphasize that its true value emerges when learning, rather than technology, takes center stage. This article introduces the Explorers of the Forest of Reading and Writing project, a blended model designed for second-grade bilingual students. Its goal is to make literacy instruction motivating, personalized, and sustainable, while closing learning gaps and strengthening students’ confidence as readers and writers.

Theory in Action: The Forest as a Metaphor for Learning

The Explorers of the Forest of Reading and Writing project is grounded in an educational vision that integrates theory and practice to transform literacy in bilingual contexts. Its design applies the insights of key educational thinkers and cognitive scientists who remain relevant in the 21st century. From Dewey (1938), the concept of active, meaningful learning is adopted; from Bruner (1960), the idea of discovery and the spiral nature of knowledge; and from Vygotsky (1978), the notion of social mediation as a driver of development. It draws on Piaget’s (1952) stages of cognitive development, as well as Schank’s (1999) emphasis on prediction, modeling, and reflection. Together, these perspectives shape the forest as a space where students move beyond reading and writing to become active explorers of their own learning.

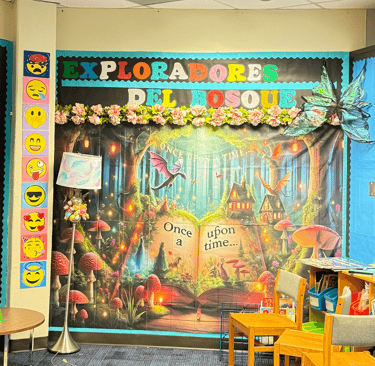

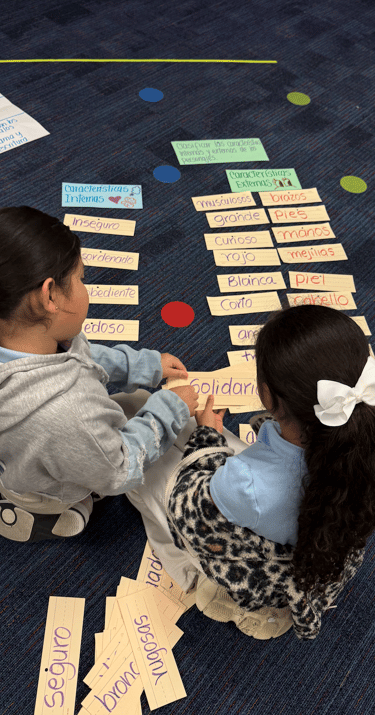

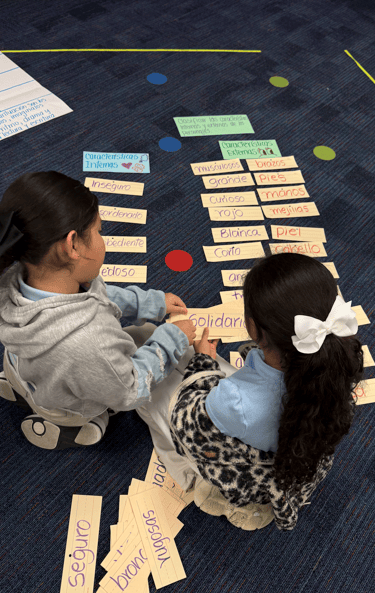

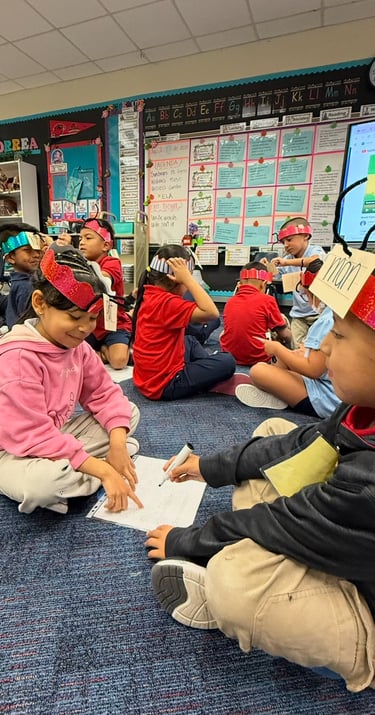

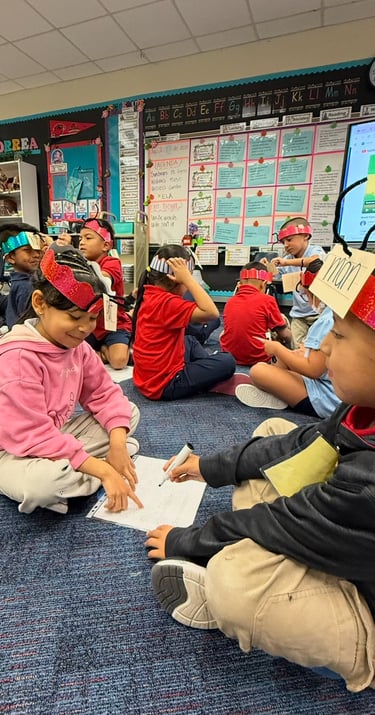

The Forest of Reading and Writing integrates English and Spanish literacy, ensuring curricular alignment, linguistic balance, and cross-linguistic transfer (Cummins, 2000). Each week, students engage in a mix of physical and digital learning experiences, earning tickets and collecting “forest coins” that can be exchanged in the forest store as part of a gamified recognition system. When combined with meaningful literacy tasks, these elements strengthen students’ intrinsic motivation and perseverance (Deci & Ryan, 1985). Within this model, learners are celebrated as explorers of their own journey, progressing through color levels that turn goals into a series of challenges and achievements.

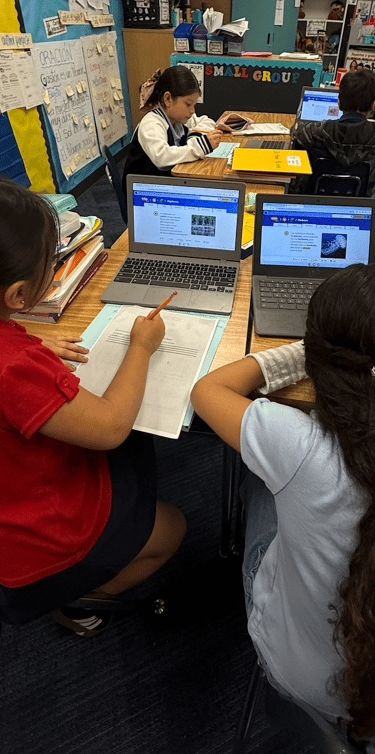

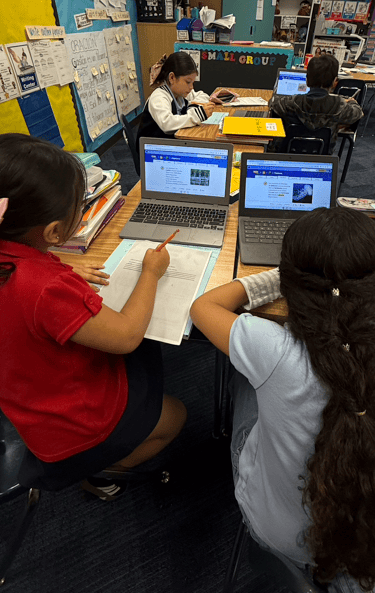

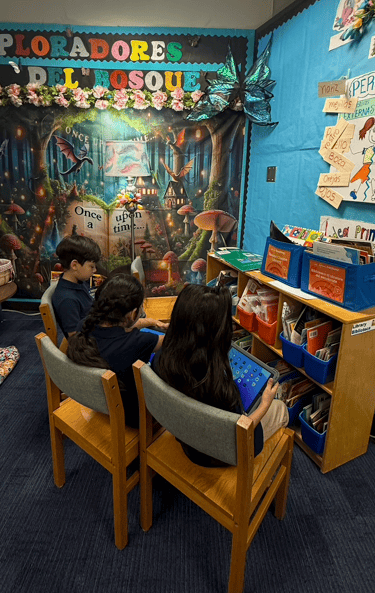

Learning unfolds through a variety of interactive spaces that blend imagination with pedagogy. Each station invites students to engage with literacy from multiple perspectives, reading stories, crafting texts, exploring sounds, using digital tools, and creating projects that make learning visible. Cozy reading corners, collaborative writing zones, and playful word workshops transform routine tasks into meaningful experiences that promote comprehension, creativity, and perseverance (Guthrie & Wigfield, 2000). These interactive environments also reflect the principles of Universal Design for Learning (CAST, 2018), demonstrating how structure and play can coexist to build bilingual literacy and authentic engagement.

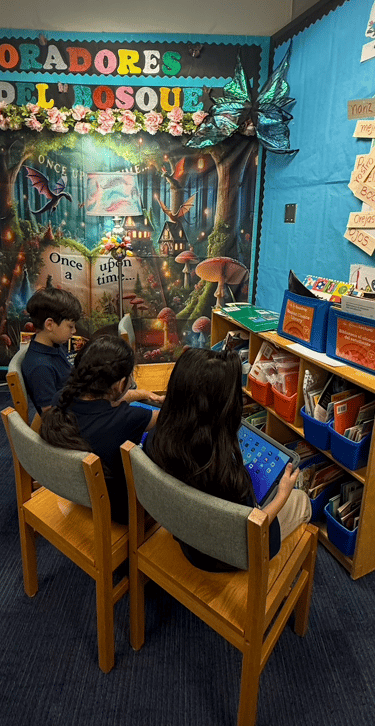

Personalization has emerged as a key element in this model. In the Forest Fairy’s Refuge, small-group instruction tailored to each learner’s needs provides close guidance, fostering literacy growth and confidence (Brookhart, 2013). As students rotate through digital and face-to-face stations, differentiated instruction merges with collaborative and autonomous learning. Creativity and imagination, central to spaces such as the Writer’s Cave and the Inventors’ Path, enhance academic and socio-emotional skills (Galinsky, 2010; Wagner, 2010). Moving forward, the action research process seeks to extend these strategies to additional grade levels, explore how gamified rewards can nurture resilience and a growth mindset (Dweck, 2006), and further document how bilingual integration promotes sustainable cross-linguistic literacy (Cummins, 2000).

Vision: Learning to Read and Write on a Magical and Challenging Path

The Forest of Reading and Writing envisions bilingual literacy as a meaningful and inclusive journey where every child becomes an explorer who advances step by step through joyful challenges in reading and writing. Technology serves as a bridge to deep learning, motivating, personalizing, and expanding opportunities for discovery. When integrated with a clear pedagogical purpose, it enhances both motivation and academic understanding (Hughes & Roblyer, 2022). As Christensen, Horn, and Johnson (2017) explain, disruptive innovation emerges when digital tools transform learning, empowering students to take active ownership of their progress.

To bring this vision to life, the Forest of Reading and Writing is supported by a dynamic ecosystem of digital tools that strengthen motivation, personalization, and creativity in the bilingual classroom. Platforms such as i-Ready, Amplify Reading, Schoology, PebbleGo, Kahoot!, Adobe Express, and Genially act not as isolated resources but as catalysts for deep learning when intentionally aligned with pedagogy. Used purposefully, these tools personalize instruction, foster collaboration, and empower students to express themselves as readers, writers, and creators. In this way, blended learning serves as a bridge between creativity and rigor, demonstrating that digital innovation grounded in pedagogy leads to meaningful and sustainable growth in literacy (Graham, 2019).

Together, these digital resources demonstrate that technology extends beyond motivation; it broadens the ways students learn, create, and share knowledge. When intentionally integrated into hybrid environments, they enhance participation and strengthen reading comprehension, writing, and cross-linguistic transfer. As Hughes and Roblyer (2022) note, technology transforms teaching when guided by clear pedagogical goals. Similarly, Graham (2019) explains that blended learning accelerates innovation by providing personalized and sustainable learning experiences. Finally, Lombardi (2007) reminds us that digital resources, when embedded in authentic contexts, prepare students to solve real-world problems and develop essential competencies for the 21st century.

The Forest of Reading and Writing provides a practical and replicable framework for transforming bilingual literacy, benefiting not only students but also teachers, curriculum specialists, and school leaders. By integrating adaptive digital tools with physical stations and gamified dynamics, the model demonstrates how to sustain motivation and engagement in diverse classrooms with differentiated needs, while emphasizing the importance of personalized feedback as a key driver of learning and confidence (Brookhart, 2013). The forest functions as a living laboratory where effective strategies can be modeled, shared, and adapted across educational contexts.

Practices such as close feedback in the Forest Fairy’s Refuge, personalized instruction through platforms like I-Ready and Amplify, and playful stations like the Writer’s Cave and the Inventors’ Path serve as tangible examples that other educators can replicate. In doing so, the forest not only validates its classroom impact but also cultivates a collaborative network among teachers, specialists, and school leaders, fostering creative, challenging, and sustainable learning communities (Creswell & Creswell, 2018).

Reflections from the Forest: Growing as a Teacher and Learner

Since the implementation of the innovation plan, there has been a gradual increase in students’ participation and motivation to engage in more reading and writing activities. Although tangible results are still emerging, early observations suggest a growing curiosity and willingness to learn. These initial signs indicate that motivation and interest in literacy are beginning to strengthen, an encouraging step toward fostering a sustained love for reading and writing (Guthrie & Wigfield, 2000). This process remains part of an ongoing cycle of reflection and improvement characteristic of action research.

My teaching role has evolved from delivering content to designing meaningful, student-centered experiences guided by the COVA and UDL frameworks (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005). Challenges such as limited infrastructure and the need for ongoing professional development have been addressed through a balanced use of digital and print resources, as well as through modeling and coaching sessions (Graham, 2019). Family participation, supported through ClassDojo updates and short videos, has continued to grow as a crucial factor for sustaining innovation and helping students transfer literacy skills beyond the classroom (Barron & Darling-Hammond, 2008).

Conclusion: The Forest as a Future of Literacy Innovation

The Forest of Reading and Writing demonstrate that bilingual literacy can become a joyful, challenging, and inclusive experience when the richness of physical stations is combined with the power of digital resources. More than a methodological strategy, it represents a paradigm shift that positions students as active explorers of their own learning, allowing them to move at their own pace, overcome challenges, and discover reading and writing as meaningful adventures. Within the framework of participatory action research, early findings suggest that this model has the potential to reduce gaps in motivation and performance while strengthening students’ confidence and autonomy. Its greatest value lies in being a flexible, replicable approach that teachers and educational communities can adapt to their own contexts, honoring students’ cultural and linguistic diversity.

The call is clear to innovate in literacy by creating environments where children not only learn to read and write but also see themselves as protagonists of their own stories. As Wagner (2010) reminds us, students need skills for the future, and Galinsky (2010) adds that such skills are nurtured in childhood through creativity, perseverance, and collaboration. Every forest we cultivate in our classrooms becomes a seed of educational transformation, capable of inspiring new generations.

I invite you to download the full Article.

DOCUMENT PDF

REFERENCES

August, D., & Shanahan, T. (Eds.). (2006). Developing literacy in second-language learners: Report of the National Literacy Panel on language-minority children and youth. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Barron, B., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2008). Teaching for meaningful learning: A review of research on inquiry-based and cooperative learning. George Lucas Educational Foundation.

Brookhart, S. M. (2013). How to create and use rubrics for formative assessment and grading. ASCD.

Bruner, J. S. (1960). The process of education. Harvard University Press.

CAST. (2018). Universal Design for Learning guidelines version 2.2. CAST. https://udlguidelines.cast.org

Christensen, C. M., Horn, M. B., & Johnson, C. W. (2017). Disrupting class: How disruptive innovation will change the way the world learns (Expanded ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). SAGE Publications.

Cummins, J. (2000). Language, power and pedagogy: Bilingual children in the crossfire. Multilingual Matters.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum Press.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. Macmillan.

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

Galinsky, E. (2010). Mind in the making: The seven essential life skills every child needs. HarperCollins.

Graham, C. R. (2019). Current research in blended learning. Educational Technology Research and Development, 67(4), 1003–1008. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-019-09744-1

Guthrie, J. T., & Wigfield, A. (2000). Engagement and motivation in reading. Handbook of Reading Research, 3, 403–422. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hughes, J. E., & Roblyer, M. D. (2022). Integrating educational technology into teaching: Transforming learning across disciplines (9th ed.). Pearson.

Lombardi, M. M. (2007). Authentic learning for the 21st century: An overview. EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative. https://library.educause.edu/resources/2007/1/authentic-learning-for-the-21st-century-an-overview

Piaget, J. (1952). The origins of intelligence in children. International Universities Press.

Schank, R. C. (1999). Dynamic memory revisited. Cambridge University Press.

Wagner, T. (2010). The global achievement gap: Why even our best schools don’t teach the new survival skills our children need—and what we can do about it. Basic Books.

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design (Expanded 2nd ed.). ASCD.